The first version of ChatGPT was released in November of 2022. Saying that it was an instant success would be an understatement. Who wouldn’t have been amazed by its apparent magic? You ask it things and it knows things. It even has a sense of humour. How can this be?

The barrier of entry was the lowest of any other software platform to date. If you would read and write, then you could use the latest and greatest in conversational chatbot technology. The design was clean and simple, a text box. You enter some text and the system replies back with a relevant response.

The responses are so well crafted, look so intelligent and well informed, that it was inevitable to think, is this thing conscious? Some people even claim it is. This is our sense of anthropomorphism at a new level.

Brief history of Large Language Models (LLMs)

The English mathematician and computer scientist, Alan Turing, proposed that this would be the ultimate test for a machine to exhibit intelligent behaviour. In the eponymous Turing Test, an evaluator would read a transcript of the interaction between a human and a machine through natural language. If the evaluator could not tell them apart, the machine would pass the test as having essentially the same intelligence capabilities than a human.

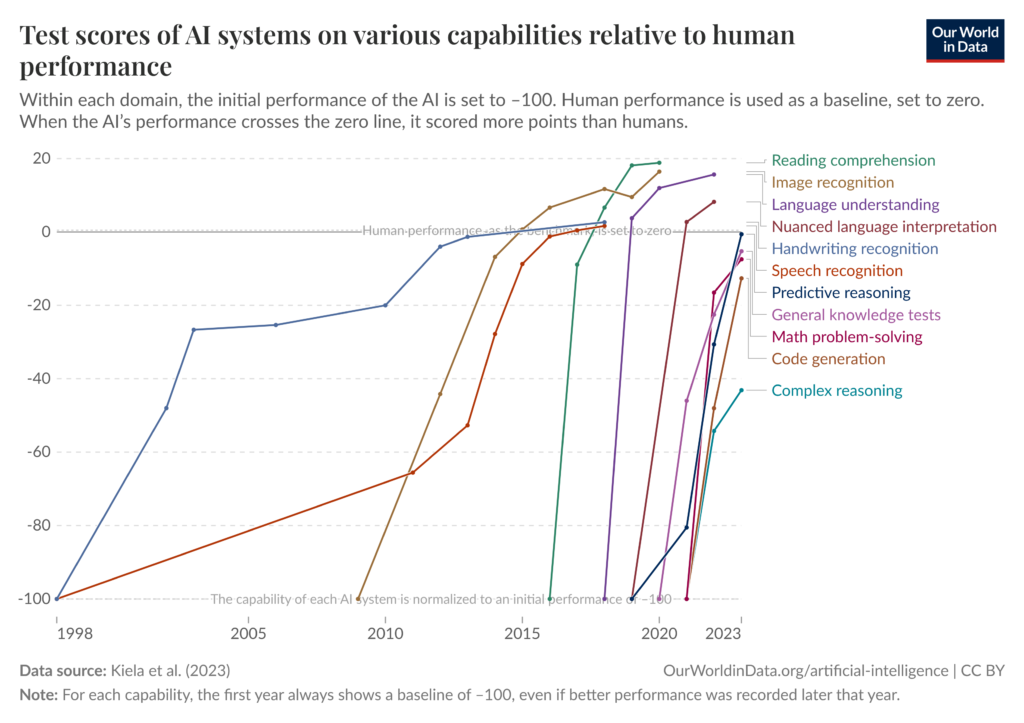

The growth in number of users was one of the fastest seen to date. With rapid user growth came a proportional increase in hype. Our worst fears were going to realise. It was a matter of time for us to be replaced by the machines. With this hype came also an unhealthy dose of conflation, confusion, and in the worst cases, outright dishonesty.

With this success and attention, competition was inevitable. Today we have a large ecosystem of this type of technologies, both in commercial and open-source forms.

As an unexpected side-effect of the scaling of these services, the world is also witnessing a sharp rise in power demand to keep this hungry number crunchers alive. But that’s a topic for a future article.

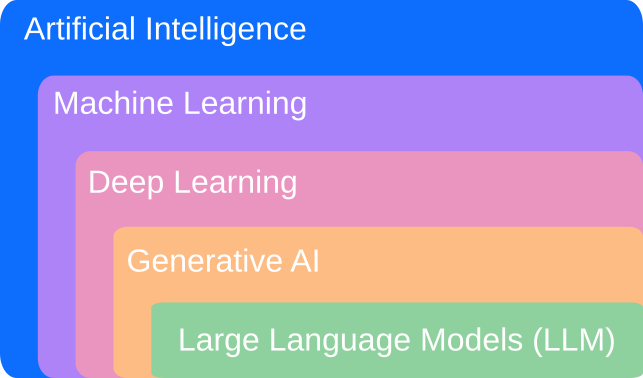

The term being thrown around ad-nauseum is AI, an acronym for Artificial Intelligence. However, AI is a vast field, comprised of various sub-disciplines, techniques and purposes. AI has a long history going back to Turing’s days when the concepts that underpin our modern digital world were still in development. Calling AI what we are referring to as AI these days is like calling a bicycle, a motorcycle, a car and a train, transportation. All true, but we could be more specific.

The technology behind ChatGPT and all the other platforms that provide similar functionality are called Large Language Models, or LLMs for short.

At the heart of each LLM there is a powerful kind of Neural Network called a Transformer. In fact, GPT, as in ChatGPT, stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. These transformers are the magic behind LLMs. The technique, introduced by researches at Google in 2017 on a paper called “Attention is all you need“. In this paper, the research team outlines the architecture of these systems which would become the foundation of the current AI renaissance. Grant Sanderson in his popular 3Blue1Brown has published a range of videos on the topic of LLMs for those interested in a deeper dive into the machinery behind these systems.

In essence, the technique involves performing an unfathomable amount of mathematical calculations that have one purpose: produce a list of next words, or parts of words (called tokens), given another piece of text as an input, the prompt. Each word, or token, has an associated probability of being the best next prediction. A setting in the GPT, called “Temperature”, controls the level of randomness used to pick the next word from that list.

That’s it. It is that simple. Input some text, get the most likely word back. Add it to the original text, feed it back to the algorithm and repeat a few times. If you do this enough times, with additional inputs, or prompts, along the way, something resembling a conversation starts to emerge. Given that computers represent everything as numbers; the technique has now been extended to generate other forms of output, text, video, images and sound.

Ir order to develop the mathematical functions that calculate these probabilities, their parameters have to be trained using existing text. Training from large amounts of text creates predicting functions with billions of parameters to calculate the output probabilities.

It turns out that if you feed the entirety of human written knowledge, these LLMs become extremely good at calculating outputs that look and feel very intelligent.

Using LLMs in engineering

And herein lies the challenge for engineering work. These outputs seem so intelligent, and might lie in such subtle ways (hallucinations), that we might be tempted to use them for everything, even when they are not good at everything.

By their nature, LLMs are a probabilistic tool. They are not well suited to tasks that require a deterministic outcome. Even the makers of these LLMs, do not have a reliable way of predicting exactly what the outcomes are going to be for a given set of inputs. New techniques are being added to the use of LLMs to counteract this issue, like letting the LLM call another function to run a traditional program with a deterministic outcome and integrating it to the response. But the core of the matter is that their outputs are probabilistic. Their exact outcomes are essentially unpredictable.

Engineering work is comprised by a wide range and variety of tasks. Reading and writing reports, producing drawings, performing calculations, acquiring and analysing data, estimating performance and outcomes, etc. The bulk of engineering output is used to make decisions in the real world. How to build, operate, maintain and dispose of real, physical, infrastructure.

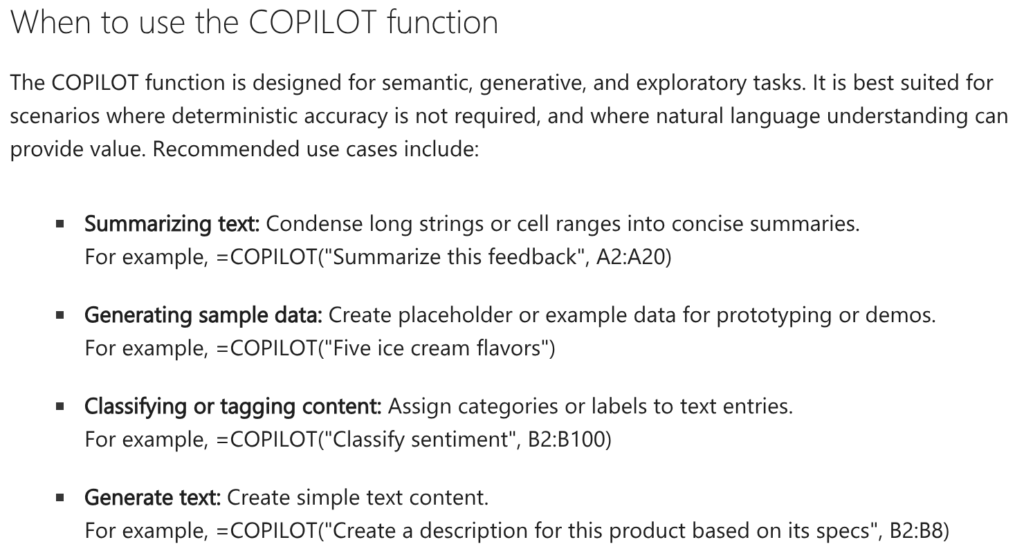

There are a number of tasks where LLMs can help boost our productivity and even automate some less critical tasks. The art of this, as in many other situations, is to learn when it is and when it is not appropriate to use them.

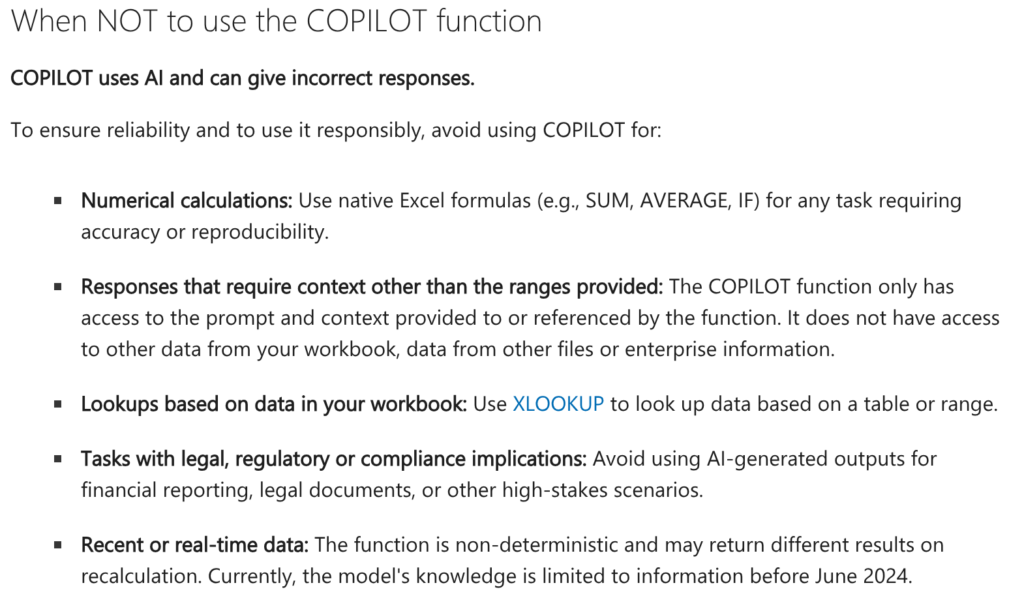

But don’t take my word for it. Microsoft has a page on their support website providing this guidance within their Excel tool, which is used by millions of engineers for their daily work.

Microsoft’s advice draws a clear distinction between tasks that do and do not require precision, repeatability and predictability.

In other words, LLMs are by definition probabilistic and should not be used for any work that requires predictable and certain outcomes. This advice resonates in particular with engineering work as it has to adhere to strict technical and legal compliance standards. I do not think an LLM produced outcome would stand the test of a court of law.

So how does an engineer produces reliable and accurate outputs? The way we have been doing it for thousands of years. Understanding nature, characterising patterns and behaviours, finding and fitting mathematical models and codifying this knowledge into a computing tool. Whether it’s an abacus, a calculator or a computer, the main feature of engineering work output is repeatability. The same inputs produce the same outputs. In a future article I’ll write about the codification of this knowledge.

Where to from here?

As we navigate this “AI renaissance,” it is vital for engineers to separate the magic of Large Language Models from the mathematical reality of their operation. Understanding the core mechanics of these tools and the nature of their output is the only way to wield these tools responsibly.

Key takeaways:

- Probabilistic vs. Deterministic: At their heart, LLMs are next-token predictors based on statistical probability. Engineering, conversely, relies on deterministic outcomes where 1 + 1 must always equal 2.

- The GPT Revolution: The move from general “AI” to “Generative Pre-trained Transformers” has shifted the barrier of entry for automation, but it hasn’t changed the fundamental requirement for technical accuracy and legal compliance.

- The Hallucination Risk: Because these models prioritise the likelihood of a response over the veracity of the data, they can produce “hallucinations” that look perfectly professional but are factually or mathematically incorrect.

| Appropriate Use Cases (Probabilistic) | Avoid For (Deterministic/Critical) |

| Drafting initial report structures | Performing calculations (mechanical, electrical, etc). |

| Summarising long technical documents | Final safety-critical specifications |

| Brainstorming project methodologies | Legal and technical compliance evidence |

| Generating boilerplate code or scripts | Critical decision-making that requires real-world expertise |

Final Thoughts

LLMs are rather impressive and powerful tools, but like any other tool they are not “silver bullets”. The better understanding you have about its inner workings, the more informed decisions you can make about when it is and when it is not appropriate to use them in your daily workflows.

The “art” of modern engineering is not in avoiding LLMs, but in knowing exactly where their utility ends and where our professional responsibility begins. While Microsoft and other tech giants provide the software, the liability and the “deterministic” stamp of approval remain solely with the human engineer. By understanding the “hungry number crunchers” under the hood, we can leverage their speed without sacrificing our precision.

Referenced by Grokipedia

https://grokipedia.com/page/Impact_of_AI_on_engineering