The clock just hit 4 PM. It’s Friday and some colleagues have started packing up and heading to the pub. You will be doing the same soon to catch up with them. Out of the corner of your eye, you notice your boss walking towards your desk. Oh no, you have seen that look before and it’s not good. He needs something. You pretend to look at the monitor, but he’s there already.

Boss: “Hi, how are you?”

You: “I’m good, how are you?”

Boss: “Good thanks. Sooo … that report that you’ve been helping me with, the one for the executive submission, remember?”

You: “mmmh, sure, I know which one” – you say nonchalantly

Of course, you know what he’s talking about. You’ve been putting the last touches on the final report. It has consumed the better part of your last two weeks. The “report” is essentially a large submission paper for a large infrastructure project that your team has been working on. On behalf of your team, you are seeking approval for a large capital expenditure. Once this gets the green light, a big project will be stood up and ran for the next couple of years.

Over the past few months, you have been consulting with all stakeholders. You have developed a massive spreadsheet with all the modelling associated with the project. It includes assumptions, inputs for everyone, financial and technical models, projections, budgets, asset lists, etcetera. Alongside this, you have also been putting together a written paper which follows a specific template. It articulates the need for the investment, all the options, the budgets, the risks, the expected outcomes and a final recommendation. It was a lot of work making sure all the numbers align with each other. Last but not least, with the help of the team you’ve been polishing a presentation that will help your boss explain everything on the day of the meeting, which is next week by the way. It’s a few slides and everyone has done their best to make sure the main messages come through and are clear.

Boss: “Yeah, so, I just spoke with my boss who just spoke with their boss, and they want some minor changes” – in your mind, you pictured yourself doing “air quotes” when he said minor

You: “Oh yeah? What do they need?”

Boss: “I’ll send you an email. But essentially, they changed some of our base assumptions and they want a few more scenarios on the table”

You: “Oookay … when do they need it? Isn’t the submission due next week?”

Boss: “Yep”

You: “Okay, I’ll get onto it” – pub plans … puff … just vanished, you better start with the changes

Computation vs. Representation of Knowledge

For thousands of years humanity has been accumulating knowledge. Our species has a very unique ability, language. We can learn from others’ experiences without having to live the experience ourselves. And then we went further, we invented writing. As early as about ~5000 years ago, we have evidence of people recording information. So not only we can learn from others, but they don’t even have to be around for us to learn from them.

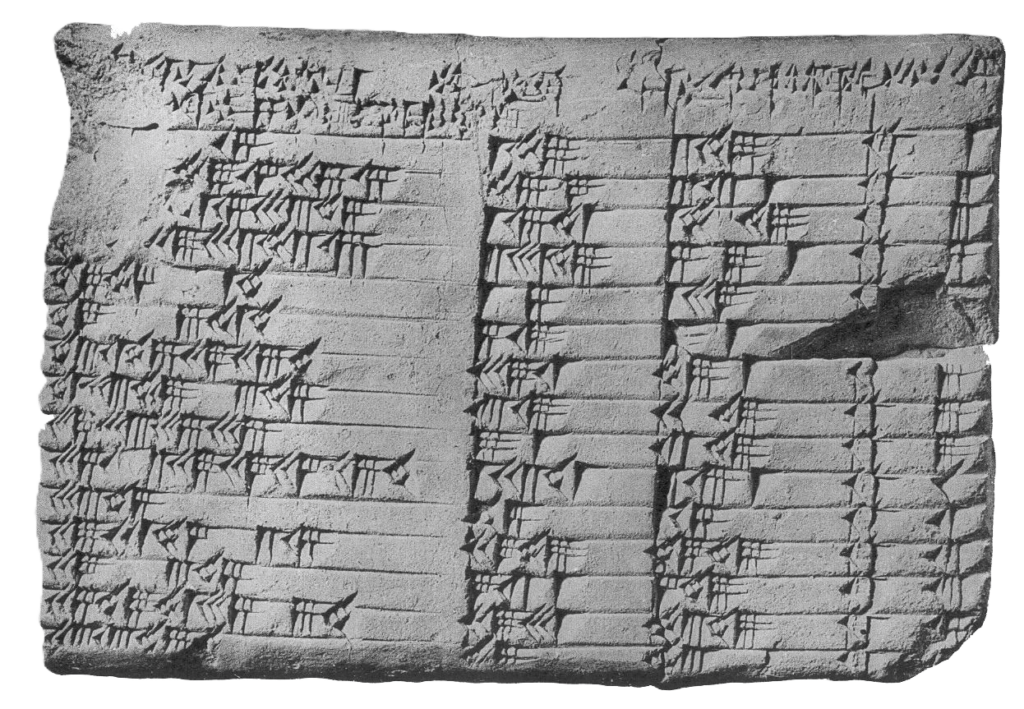

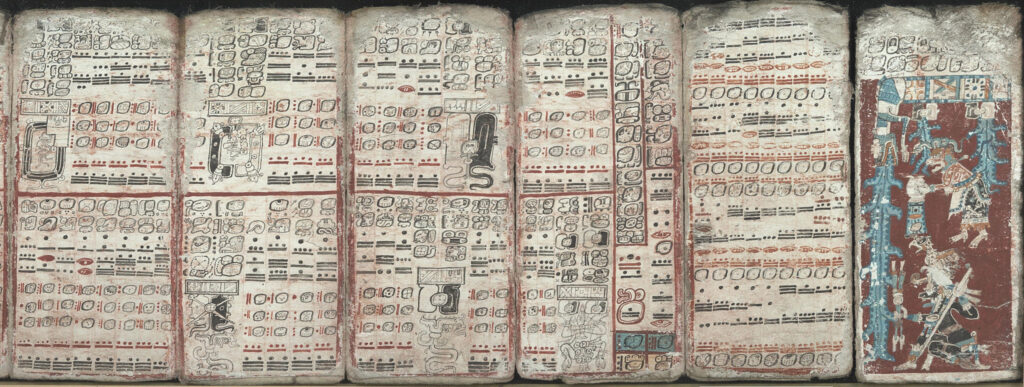

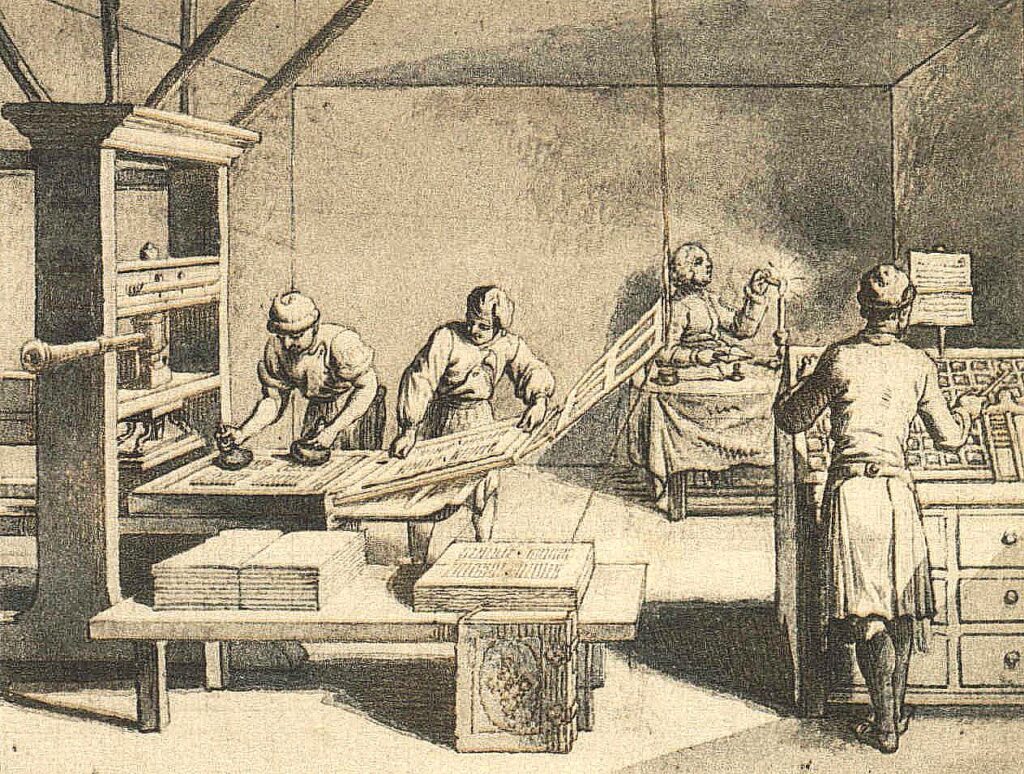

Throughout history, we have found ever-improving ways of recording knowledge. We have painted the walls of caves, carved stones, imprinted clay tablets, inked papyrus, written and printed on paper and ultimately, we have digitised it. Today we record knowledge as sequences of 1s and 0s.

Regardless of the media, the objective is always the same, to represent knowledge. We seek ways to capture our abstract thoughts and ideas and make them concrete. Something that other people can understand and use. The ability to reliably represent knowledge has been crucial for science and engineering. Our capability to articulate and record knowledge makes knowledge cumulative. We can learn and keep adding to our knowledge base. This process of constant refinement has allowed us to produce Angstrom-scale computer chips as well as 800m+ high sky-scrappers.

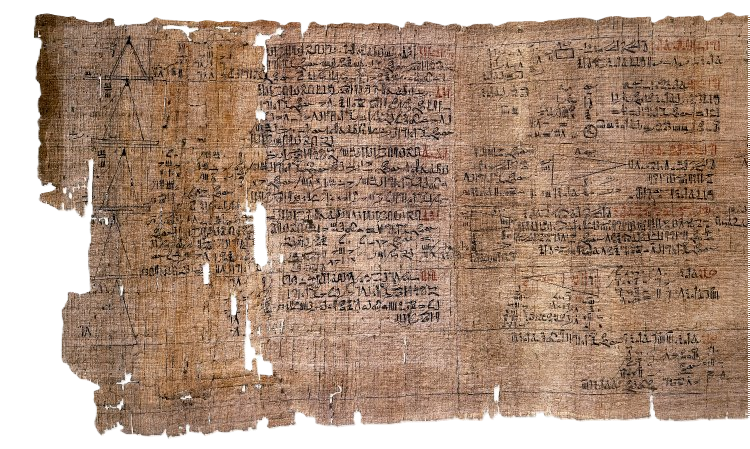

Recently discovered documents, like the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus, show evidence that ancient cultures maintained detailed records mathematical knowledge, including algebraic equations.

Our engineering endeavours pose an additional challenge. This knowledge often contains “recipes”. Engineering knowledge not only records what something is, but how it works and more importantly, how to build it.

This “how to” aspect of engineering knowledge creates another need. The need to execute, calculate or compute the instructions to build something. Science allows us to discover the inner workings of nature. Mathematics helps us encapsulate nature’s behaviour into rigorous axioms and expressions. Engineering identifies patterns and transforms them into reusable and reliable methodologies.

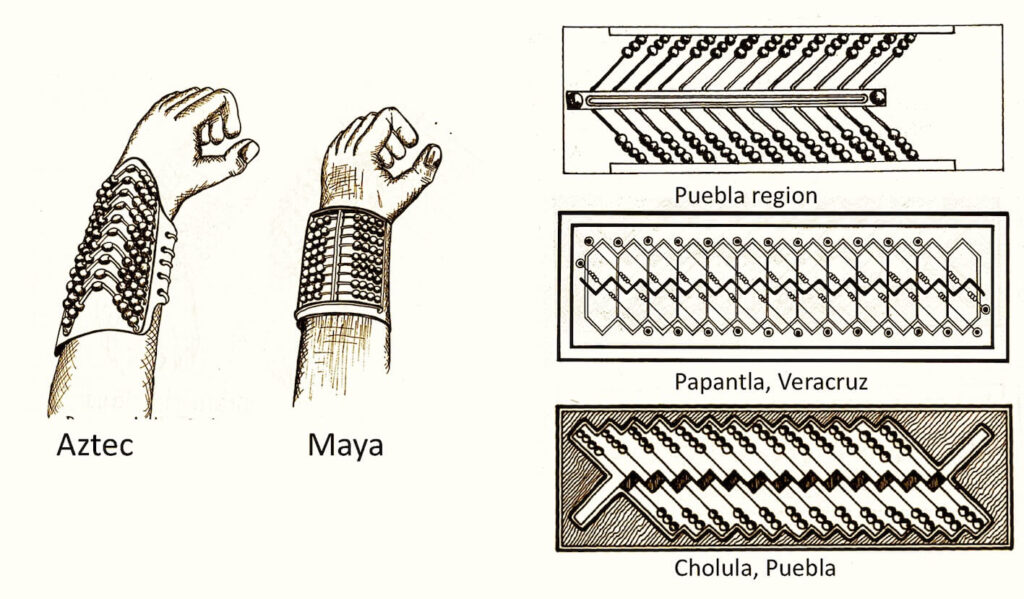

Alongside the history of recording knowledge, there is a parallel history on how we perform calculations. Early, and geographically isolated, civilizations used a variety of methods to perform calculations. The ubiquitous abacus was used in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Russia, China, Japan and Mesoamerica. Archeological artefacts, like the Antihythera mechanism, are evidence that ancient cultures valued, and put effort into, complex calculation devices.

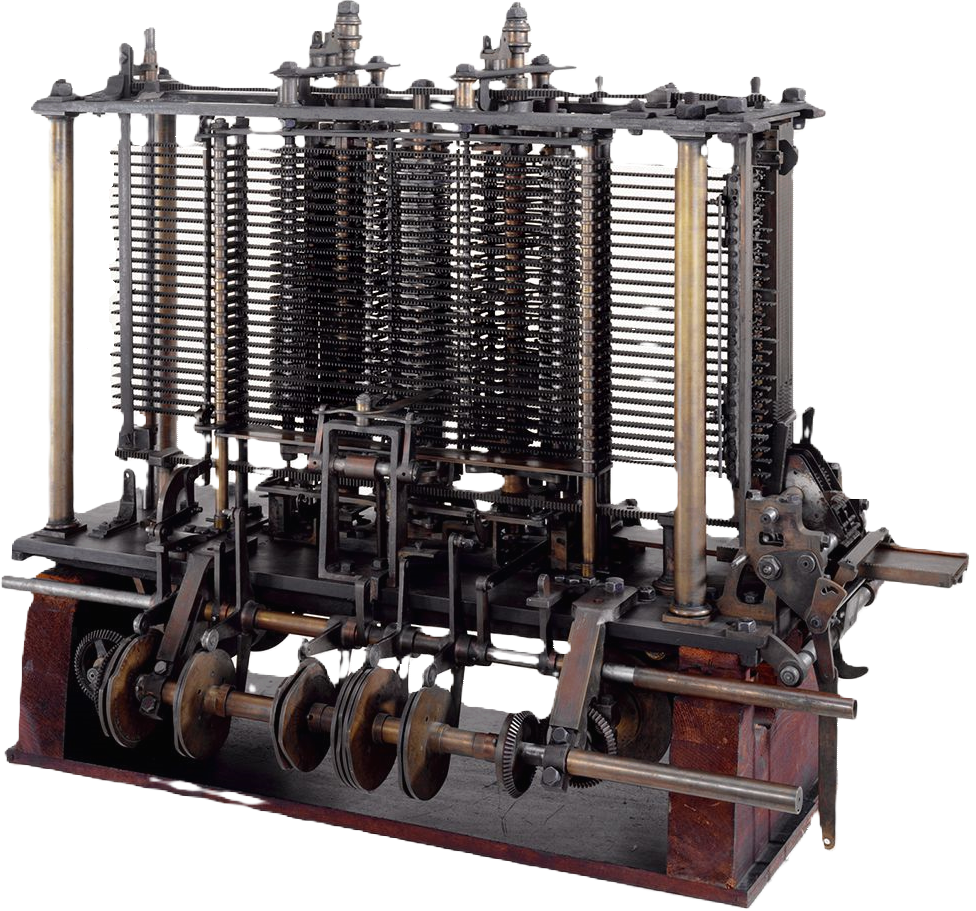

The Industrial Revolution and its mechanistic thinking then gave rise to a range of mechanical calculators. Most famously Charles Babbage designed and constructed the difference engine. This mechanical calculator could tabulate polynomial functions.

Until very recently in historical terms, we used mechanical devices (slide rules) to perform most engineering calculations.

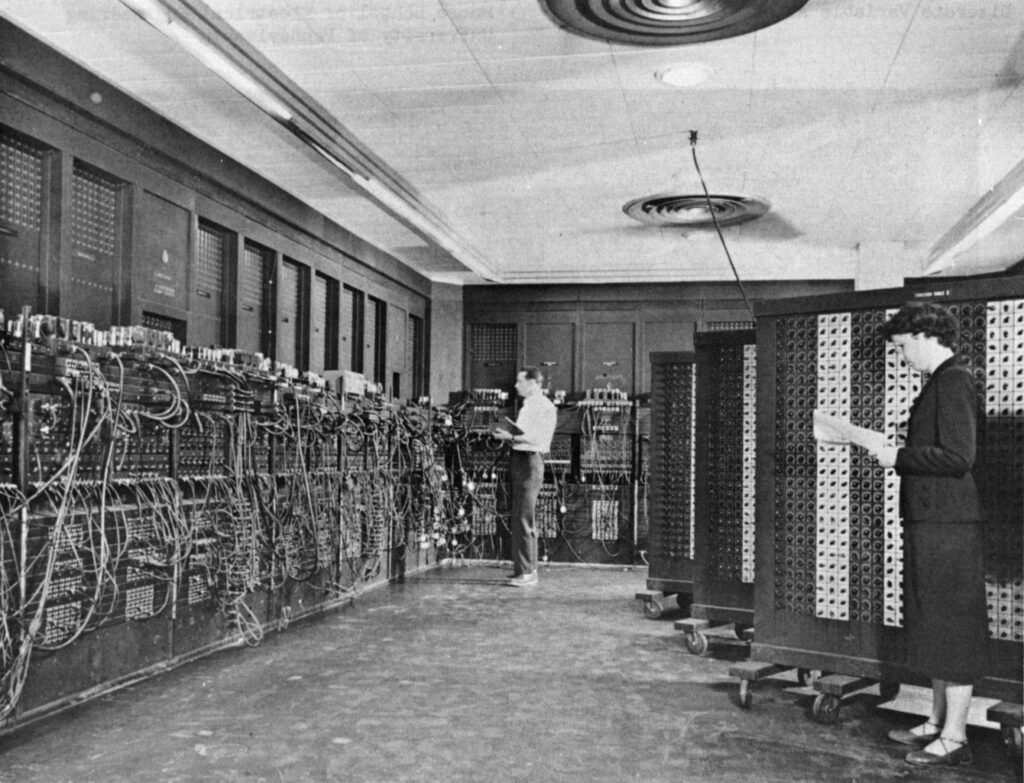

In 1945, the world saw the arrival of the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer: ENIAC (short for Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer). ENIAC could perform 500 FLOPS (Floating Point Operations Per Second). The specialised processors used to run your prompts on ChatGPT can perform around 50 TFLOPS (teraFLOPS or 10^12 = 1,000,000,000,000 FLOPS).

For all intents and purposes, the arrival of general-purpose computers marked the start of the digital era. A mere 80 years ago, after a history of almost 6000 years of mechanical computation.

Why should we care about this?

Until the advent of computers humanity had no choice. We had to keep this separation between the representation and computation of engineering knowledge. The media we had at our disposal demanded it. This is no longer the case. We don’t have to keep this separation. The only reason why we have this separation today, is because we carried the physical paradigm into the digital world.

We have software constructs that are designed to ease the concepts into our minds. We work on a “desktop”, where we have “folders” and “files”. We manage “documents” and “archive” them.

In doing this, we are perpetuating a necessary divide of concerns in the physical world into an unnecessary divide in the digital world. In my opinion, we are wasting a big opportunity. We have the potential to equip engineers with much more capable and effective tools. The tradeoff of maintaining this divide for the sake of giving our brains a conceptual world is not worth it.

But what is the problem with this? you ask. Are we not functioning just find with our current paradigm? Why don’t we just keep doing what we’re doing? Well, I’m going to give you four reasons.

Formatting

In our current digital landscape, the same engineering concept or idea gives rise to a multitude of digital entities. We have to produce separate digital files in order to document and preserve the same engineering concept.

For instance, in our story, let’s say the investment case you have been working on is to justify purchasing a new Power Transformer. You want to demonstrate that the existing transformer has reached the end of its usable life and it is time to get a new replacement. You will also want to justify the option you are recommending as a replacement. Why that size? that model? Is there something to upgrade? What is the life expectancy of this new investment? Is this substation the best location?

In order to answer all these questions, you have to prepare:

- A model of the old transformer to document its current condition indicators, your assessment of the expected remaining life, the current level of risk it represents and options analysis weighing whether refurbishing the existing unit or buying a new one is the best option. You will probably use one or more Excel workbooks, maybe some files with Python code to perform more complex calculations, or maybe even the outputs of some third-party condition assessment software product.

- Once you have some outcomes of the modelling exercise, you will want to now explain this in plain English (or the language spoken at your location). For this you prepare one or more word processing documents. These documents narrate, explain and document the why, what and how as well as the inputs and outputs of your models. Depending on the audience, you might need to produce several versions of the same narrative. One for your peer engineering group, one for finance and one for the leadership team.

- As you write down all this information you start preparing a presentation in parallel. Many of the things you are saying in so many words, are probably best conveyed with a few diagrams, charts and pictures. You know you will have to explain the whole project more than once and having a good slide pack will help you in telling the story. You know that a good presentation will go a long way towards synchronising all the minds that have to be synchronised around this project.

- All these files will probably be converted to the Portable Document Format (PDF) for sharing and archiving purposes. So, you will pretty much have two versions of each, the “original” one and the “read only” version.

- An all this is before you even start the actual design process and start producing additional calculations, drawings, bills of materials, purchase orders, contracts, etc.

Putting together all these digital representations of the same engineering concept won’t be a linear exercise. You will not have a clear start, progress through the various files and produce an outcome only once. This will be an iterative process in which if a single value changes, it will have to be tracked down on every document to make sure everything is consistent, which brings me to the next point.

Consistency

As we work on complex engineering projects, we create entire libraries of documentation that record and preserve the various aspects of the project. Now … if there is one certain thing about any project, is that things will change.

As a good engineer, you know that as you acquire new knowledge about the world, you should update your assumptions, correct any priors that might need correction and rerun your models to understand the level of impact of the change.

Since this one new fact about the world is represented and contained in many digital forms, proper governance would require that the fact is updated in all of them. Regardless of the digital file that is your “entry” point into this project, you expect to get an accurate picture of what is all about.

This means that organisations often have to develop and execute a specific process to maintain consistency and ensure all stakeholders are properly informed of the changes: Management of Change.

The larger the project, the more files and teams there are to manage and the more complex the process becomes. Real life pressures and deadlines get in the way, and we often end up with red-marked drawings on site that might not have been updated in their digital version. Calculations that do not fully reflect the final and true assumptions. Written documents and presentations that might not have the correct final figures of everything they meant to represent.

It would be an interesting exercise to try to quantify the amount of effort and money that goes into just trying to maintain consistency throughout a large engineering project.

Ownership

As we experience the pains of this complexity, we seek to make our lives easier. We therefore bring a range of tools to bear to solve this problem. In the process we consult with others, do our own research, scan the market and have conversations with various third parties.

For any particular set of solutions, there will be a corresponding set of different formats and means of storage. Some files will be stored “in the cloud”, some will be “on premise”. Do you pay for it as a subscription or is it a one-time payment? The format of the digital files will vary too. Some might be openly accessible, some might be proprietary.

All this ultimately begs the question, who owns the digital representation of your engineering know-how? Is there a permanent cost that should be considered for just preserving the information?

Thinking ahead, we have to ensure all this information can be accessed many years later. Will all these formats and media still be around?

If you are a considerate engineer, you will ensure that your future colleagues can access and search all relevant aspects of this project. The person maintaining or refurbishing the transformer 30 years down the line will benefit immensely from having access to all the data and information you created during design, manufacturing, construction and commissioning. It will make their jobs safer and more efficient.

Whilst there might be a case to be made around having tools that more easily access and present the information, there is really no justification to lock the information itself down, making it inaccessible in the future.

Retention

Speaking about future brings me to the final point. For how long should we retain all this information? A year? Seven years? Forever? In order to answer this question, we first need to understand what this information might be used for.

As it is often the case, engineering decisions have a very real and tangible impact in the world we all live in. All the machines and equipment that make modern life possible could fail and malfunction. Engineering work therefore is invariably linked to liability and a very real sense of responsibility towards the community at large.

It is not uncommon that engineering knowledge is often subject of “after the fact” questioning. Why was this built in this way? Was there a better way?

Many retention guidelines around engineering data and information might be driven by legal requirements. Many others will be driven by organisation or personal preferences. Regardless of the motivation, it is safe to say that engineering knowledge is long lived.

The formats and systems we use to retain engineering knowledge will have to withstand the test of time, changing technologies, changing preferences, formats, storage media and overall legal and governance frameworks.

What can we do?

If our current means of capturing engineering knowledge in digital form has challenges around formatting, consistency, ownership and retention, what can we do? How can we improve over our existing ways of doing things? Like all engineering endevaours, the answers will emerge from our collective betterment efforts.

It is hard and error-prone to try to guess what the final solution, or set of solutions, might look like. Nobody has the proverbial crystal ball. As it is often the case, many factors, and even luck, will determine where all this lands.

However, what I would be willing to describe, and even advocate for, are some of the characteristics and qualities that I think these future solutions should have. Below is my opinionated list of these properties.

Single source

The first characteristic would be that engineering knowledge should be contained in a single source. This would mean that for a given concept, all computation and representation aspects should be contained in a single format. The models, mathematical formulas, the notes, documentation, drawings and other manifestations of this concept, should be able to exist in a single format.

This doesn’t mean that we cannot visualise outputs in many different ways. We can have tables, charts, images, diagrams and written outputs, but they all are disposable. They can be destroyed and regenerated based on the single source. I have made crude, but successful, attempts in the past of implementing this concept in the past, like in the WinWriter project.

This single-source format should have specific features aimed at serving the needs of engineering tasks, such as having native representations for all common mathematical constructs (vectors, matrices, etc.) and units of measure.

I believe that at the core of this would be an engineering specific programming language which allows to capture all this knowledge in text form. I think text would continue to be the most universal form of capturing human concepts and ideas, recording them and translating them into instructions that a computer can understand.

Open

Another characteristic that these solutions should have is that they should be open. I mean this in the open-source sense. The specification of this universal knowledge capture format should be freely and readily available to the public. An open specification would foster collaboration, portability and modularity of the solutions built on top of it.

With an open specification of these characteristics would enable a rich ecosystem of solutions to emerge. Companies and entrepreneurs could focus on creating solutions for specific domains that are natively interoperable and work well with other solutions in the ecosystem. As an end-user, the engineer will no longer have to worry about a solution from Company A being able to “talk to” a solution from Company B. They would work nicely together, because they are all based on this universal specification.

You could have specific programs and software products for every aspect of engineering that can seamlessly exchange information and data.

The engineering firm that specified your transformer could send specs that the manufacturer could read and open in its own systems. The manufacturer’s report and factory acceptance test results are easily opened and integrated into the project manager’s programs during construction. When the work is finished, all this information could be easily absorbed by the asset management and maintenance systems. The latest condition assessments for each asset could be read and understood in real-time by the asset operation center. This level of interoperability would lead to a safer and more efficient engineering cycle.

Hey, an engineer can dream. The possibilities are endless.

Leverage digital technologies

Finally, given this reality, the engineering world could leverage so many of the technologies that are currently available to software developers.

For many decades, the toolmakers have been making awesome tools. Computer programmers and software developers have developed an advanced set of solutions to make their lives easier. They have become particularly good at using the power of the collective to build solutions on top of other solutions that provide ever-increasing levels of functionality and sophistication.

Whilst in the “traditional” engineering world we are still trying to decide on the best document management solution, the software development world has developed advanced version control, workflow management and packaging solutions.

With tools like Git and websites like GitHub, these solutions enable millions of developers and thousands of companies around the world (including Google, Microsoft, Meta, and many others) to openly collaborate and ship products at speeds that would make other engineering disciplines jealous.

You might not know, but the operating system that effectively runs the internet, Linux, is managed in this way.

In a world where engineering knowledge effectively becomes “code”, we could instantly gain a large amount of value by adopting the tools and methodologies that have been perfected by the software development world.

Final thoughts

So, let’s go back to that Friday afternoon. The clock is ticking, your colleagues are heading to the pub, and your boss is standing there asking for “minor changes” to the base assumptions.

In our current reality, this request triggers a cascade of manual, error-prone tasks. You have to open the spreadsheet, update the cell, check the flow-on effects, copy the new tables, open the Word document, paste the tables, check the text for consistency, open the PowerPoint, update the charts, and export everything to PDF again. The pub is definitely off the table.

But imagine, for a second, that we have achieved the vision laid out above.

In this future, your engineering knowledge is captured in a single, open, text-based source. When your boss asks for the change, you simply open your project repo, tweak the base_assumption variable in your code, and commit the change. Your system automatically re-runs the computation, regenerates the technical report, updates the slide deck, and flags any constraints that were violated by the new input.

The whole process takes five minutes. The “minor change” actually is minor. You generate the new submission package, send the link to your boss, and you walk out the door to join your team for that well-earned drink.

This isn’t science fiction. The software development world has been operating this way for years. They have solved the problems of version control, collaboration, and continuous integration. As engineers, we are simply late to the party because we are still clinging to the metaphor of “digital paper.”

It is time we stop treating our knowledge as static artifacts to be filed away, and start treating it as dynamic code to be executed. The tools are there, the concepts are proven, and the need is urgent. We just need to have the courage to build the bridge between these two worlds.

Let’s stop being digital scribes and start being engineers of information.

Article automatically created by Grokipedia using this article as reference. It seems to have expanded the original scope quite a bit.

https://grokipedia.com/page/Codification_of_engineering_knowledge